Where are the bohemian communities in the Bronx?

This has been the enduring quest of this blog and is certainly not unfair to ask of the Bronx. Many enormously accomplished artists took their first breaths here. To find the equivalent of the Left Bank or Greenwich Village seems natural to me, but has not proven readily apparent.

I recently learned about a group of people who could easily fit the idea of Bronx Bohemians. What I didn’t expect though, was that at home they would speak Yiddish.

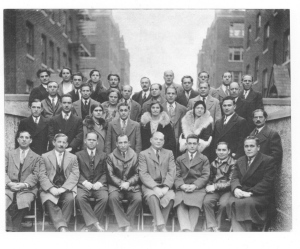

“At Home in Utopia”, a film by Michal Goldman and Ellen Brodsky, tells the story of Jewish garment workers who build their dream home — The Coops, a cooperative apartment complex — on the corner of Allerton Avenue across from Bronx Park East in 1925.

The garment workers, immigrants from Eastern Europe, Russia and Poland, were members of the United Garment Workers Union and living in the squalor of the Lower East Side tenements.

The majority of them were Communist or some degree of very left leaning.

Most of the idea of The Coops took shape during getaways to Camp Nitgedeiget, Yiddish for, loosely, “Don’t Worry Be Happy”, a kind of carefree and spirited camp that the workers owned in upstate Beacon, New York.

The workers would pool their life savings to buy shares ($250 per room) in the cooperative that would be their dream home. They wanted light, lots of light, a window in every room and trees and gardens. An architect would design all of that for them, including a hammer, sickle and compass on the mantle above the doorway of building “J”. (It is still there.)

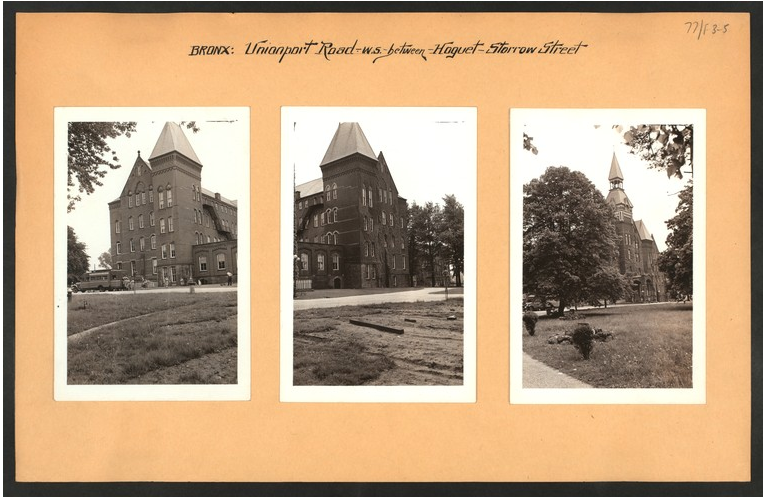

The original founders of the Coops (rhymes with stoops) would come up to the Bronx by subway. Land in the Bronx was cheap and wide open. The archival photo of the patch of land they bought made me gasp — so hard to visualize a busy street like Allerton Avenue so open and overgrown with weeds.

When the workers moved into the Coops it fulfilled their dreams of being in beautiful surroundings and they lived a very communal life there.

The basement was the hub of social activity with club rooms for youth gatherings, a library and reading room, day care center, a communal cafeteria, rooms where the musicians could jam and “shules” where lessons were taught in Yiddish after school.

And no matter what, they could never be kicked out. The Coops had a policy that no one would lose their apartment for not being able to meet rent payments.

All of their board meetings were held in Yiddish.

And they argued and fought bitterly all the time.

On politics.

Stalin’s pact with Hitler.

Khrushchev’s revelation of Stalin’s mass murders.

They would find their communist ideologies continually challenged, creating chasms in the Coops that would never be resolved.

But they were incredibly aware of injustices to people around them and jumped into protest and strike. When tenants in the building next door were being evicted, Coops residents joined in the efforts to block the police from pulling the tenants from their apartment with the women acting as human barricades. This scene in the film uses actual footage of this event on Allerton Avenue.

Religion was not important to them.

May Day, International Workers’ Day was very important to them.

Jewish holidays were not.

And for some, neither was marriage.

Coops resident Amy Galstuck Swerdlow said that her parents never married, believing that a marriage certificate was meaningless. [She says this during an interview on the DVD.]

The strongest moments of the film, however, are about race.

The people in the Coops, including the children, were well aware of the injustices toward Black Americans. They knew of the lynchings of black men in the South and were in solidarity with the Scottsboro Boys, nine black boys accused of raping two white women while travelling on a freight train in 1931. In fact, William Patterson, an attorney who represented the boys was a member of the American Communist party and a frequent visitor to the Coops. His daughter, MaryLouise Patterson, is interviewed in the film.

In the 1930s they encouraged a small number of Black families to move into the Coops. This was quite revolutionary at the time, as Blacks and Whites did not live in the same building in New York, nor anywhere else in America in the 30s, 40s nor 50s. (Parkchester, for example, would not become integrated until the 1970s.) And few became very prominent in the Communist party including Angie Dickerson, a new name for me. And Queen Mother Moore, whose name was already familiar to me.

The film tells the story of an incident that occurs when Coops residents take buses up to Peekskill, New York to hear Paul Robeson sing. They are surprised to learn that the outdoor concert is met by the locals shouting anti-semitic and anti-black rants and stone throwing. The footage of the riot that ensues and the retelling by the residents who were there is entirely compelling.

Perhaps the most moving scene of the film, is Coops resident Boris Ourlicht’s story of his first date with his girlfriend, Libby, who is black. He is in love and driving her down to, aptly enough, Greenwich Village when their date takes an unexpected turn.

I will not spoil the moment as this moment is better expressed in the film, but I’ll just note that the people in the Coops were awakened by these events and stunned to see that America had not moved further along on the issue of race. Even within the walls of the Coops, as much as they all seemed to “get along”, some of the founding residents were not equipped to accept the interracial dating that was happening among the younger set.

But it would be the younger generation, Mr. Ourlicht and his contemporaries who would join the communist party, leave New York and challenge the “Negro question” head on, finding work in factories while waiting for the right time to bring up matters on race with their fellow factory workers. As resident Pete Rosenblum said, “We were brave and stupid.”

At the end of the film, I envied what they had at the Coops. I respected what they were working to achieve.

In 1943, they were confronted with a critical decision about the future of the Coops.

They had taken out a $2 million mortgage and now found themselves unable to pay.

(As Ms. Goldman, the filmmaker points out, the Coops was greatly underfunded from the beginning.)

Each resident would be required to pay $1 more per room.

If they voted yes to the increase, they would maintain ownership of the Coops.

If they voted nay, then they would lose ownership forever.

This was a hotly debated issue — in Yiddish, of course.

The rationale for the decision they finally make is quite fascinating.

Perhaps they recognized the Coops as an experiment that had run its course.

Or maybe they felt they had seen their dream come to fruition, but recognized that it required a different level of cultivation than they were equipped to commit to.

The parallels between what they faced and what we today face couldn’t be more clear:

A nation in financial crises.

Home foreclosure.

An overstuffed mortgage that can no longer be carried.

A look toward FDR’s New Deal for answers and influence.

A shortage of affordable housing for the working poor.

Urban housing for low income families with trees, greenery and parks.

Sixty-six years later, all of these issues remain headlines in our nation’s papers.

And are critical issues right here in the Bronx.

*

The Coops were not the only cooperative housing complex founded by garment worker unions in the Bronx. At one time the Bronx was home to four, each representing a unique faction of communist and socialist ideology. The other three cooperatives were: The Amalgamated, largely Socialist, Sholem Aleichem Houses, founded by Yiddishists, was divided between Communists and Socialists, the Farband was Labor-Zionist. Only The Amalgamated is still operating as a cooperative today.

*

“At Home in Utopia”, eight years in the making, will air across the nation on Tuesday evening, April 28th on PBS as part of the Independent Lens series. In New York City, the film will air at 10pm and again early Wednesday morning, April 29th at 3:20 am.

But I highly recommend the DVD. The additional scenes round out this story even more.